Inhabiting the Christian Year: introduction

This is part 1 in a series looking at the Western Christian year (liturgical calendar). For other posts in the series, click a number: 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8.

In this series, we'll take a journey through the Western Christian Calendar. Doing so will help us see how the ancient liturgy of the church helps us "inhabit" the gospel, which is the story of the Triune God's work for our salvation, centered on Jesus. I believe that this liturgy, rightly used, is of tremendous value in helping us understand (both cognitively and experientially) the gospel as viewed through the lens of an incarnational Trinitarian theology.

Perhaps you're uncomfortable with the word liturgy---for many, it conjures up images of rigid, formulaic worship. That's unfortunate, because, rightly used, liturgy is a great aid to vibrant, life-transforming worship. In that regard, it's important to note that liturgy is biblical. The word comes from the Greek verb leitourgia, which the New Testament uses to speak of service (ministry-worship) within the church. The New Testament also uses the Greek noun leitourgos to speak of those who lead the worship of God's people (e.g. Rom. 15:16 where "leitourgos" is translated "minister"). The New Testament presents Jesus as the supreme leitourgos (Hebrews 8:1-2, KJV, where "leitourgos" is once again translated "minister").

From these Greek words comes our English word liturgy, which literally means "the service [or work] of the people." The word liturgy is then used informally to refer to the order of service by which the people of God structure worship. Given this informal definition of liturgy, all churches (whether they know it or not) have a liturgy. In some cases it's formal and highly structured (as in "high church liturgy"), in others it's less structured (as in "low church liturgy"), and in still other cases it's so informal that some churches are called "non-liturgical."

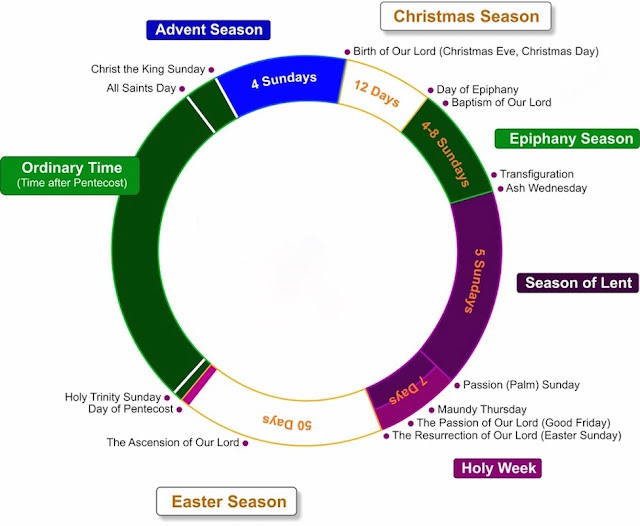

I want to emphasize here that liturgy as gospel-reenactment is not about a single Sunday worship service in isolation from the others. Instead, through a Christ-centered, gospel-shaped liturgy, the gospel story is retold as a drama that spans the course of the full year---the liturgical year (or call it the Christian year). With this integrated approach, the liturgy followed each Sunday is located within the flow of the full gospel story, unfolding over the course of the entire year through its various seasons as shown in this diagram:

As the diagram shows, the Worship Year (in the Western Christian tradition) begins in late November or early December with Advent Season followed by Christmas Season. Then comes the Season of Lent, Holy Week, Easter Season, and then a season called "Ordinary Time"---not ordinary as in unimportant, but because this season of worship addresses day-in-and-day-out Spirit-led responses to the great gospel events celebrated throughout the rest of the year. Those responses involve our participation, by the Holy Spirit, in Jesus' disciple-making mission to the world. Because that participation is led and empowered by the Spirit, Ordinary Time, which follows Pentecost, is sometimes called Time after Pentecost or Season of Pentecost.

When this year-long liturgy is followed, each worship service is themed for the season in which it falls, and in that way is deeply connected to Jesus through the retelling/reenacting of certain aspects of his story (the gospel). Optimizing that connection takes planning and creativity. It also takes time—but it's time well spent because an effective, creative liturgy engages the worshippers at multiple levels: heart, head and hands, helping them to be active participants rather than passive spectators.

The flyleaf of Living the Christian Year: Time to Inhabit the Story of God by Bobby Gross, has this to say concerning the power of liturgy to help people inhabit God’s story:

As Torrance also alludes to, in the historic worship liturgy, Communion is preceded with a prayer of confession---not to "earn” or somehow “qualify” for the distinctive blessing that comes to us at the Lord's Table---but to acknowledge the need we all have for the grace that Communion represents to people who have placed their trust in Christ. (For further detail and examples of prayers of confession, click here.)

In the next post in this series we'll begin looking at each element in the Christian Worship Year, which, as we've already noted, begins with Advent Season.

In this series, we'll take a journey through the Western Christian Calendar. Doing so will help us see how the ancient liturgy of the church helps us "inhabit" the gospel, which is the story of the Triune God's work for our salvation, centered on Jesus. I believe that this liturgy, rightly used, is of tremendous value in helping us understand (both cognitively and experientially) the gospel as viewed through the lens of an incarnational Trinitarian theology.

Some thoughts about liturgy

In this series, we'll be exploring the Christian worship year as presented in the liturgical calendar of the Western Christian Church---the calendar that serves as the organizing framework of The Revised Common Lectionary (RCL). The RCL shapes the liturgy of many Protestant and Anglican-Episcopalian denominations (Catholic and Orthodox denominations use lectionaries similar to the RCL).Perhaps you're uncomfortable with the word liturgy---for many, it conjures up images of rigid, formulaic worship. That's unfortunate, because, rightly used, liturgy is a great aid to vibrant, life-transforming worship. In that regard, it's important to note that liturgy is biblical. The word comes from the Greek verb leitourgia, which the New Testament uses to speak of service (ministry-worship) within the church. The New Testament also uses the Greek noun leitourgos to speak of those who lead the worship of God's people (e.g. Rom. 15:16 where "leitourgos" is translated "minister"). The New Testament presents Jesus as the supreme leitourgos (Hebrews 8:1-2, KJV, where "leitourgos" is once again translated "minister").

From these Greek words comes our English word liturgy, which literally means "the service [or work] of the people." The word liturgy is then used informally to refer to the order of service by which the people of God structure worship. Given this informal definition of liturgy, all churches (whether they know it or not) have a liturgy. In some cases it's formal and highly structured (as in "high church liturgy"), in others it's less structured (as in "low church liturgy"), and in still other cases it's so informal that some churches are called "non-liturgical."

The benefits of a Christ-centered, gospel-shaped liturgy

One of the great benefits of having a clearly thought-out, consistent liturgy, is that it aids a congregation in focusing its worship. But what should that focus be? The value of the historic liturgy of the Christian church is that its focus is Christ and his gospel. The RCL reflects that focus---both in its Scripture readings for each Sunday and certain other high days (which are then, typically, unpacked in the sermon), and in its following of annual celebrations of the great events in the life and ministry of Jesus. Utilizing the RCL thus helps in forming a liturgy that points to and exalts Jesus by re-telling (re-presenting) the gospel, which as the apostle Paul notes, is “the power of God that brings salvation to everyone who believes….” (Rom. 1:16). Following a Christ-centered, gospel-shaped liturgy week-to-week is a powerful way to help people think more like Jesus and, by the transforming power of the Holy Spirit, become more like Jesus.Reenacting/inhabiting the gospel story

What I am advocating (and will seek to demonstrate in this series) is an approach to liturgy that is not merely an “order of services” with certain elements to be checked off a list. The approach I'm advocating views liturgy as the "script" of a life-transforming dramatic reenactment of the gospel—the story of Jesus. This approach helps worshipers to not merely hear the story, but to inhabit the story in such a way that the story of Jesus becomes their story. As that happens, by the power of the Spirit, one's whole being---heart, mind and body---is converted (conformed) more and more to Jesus.I want to emphasize here that liturgy as gospel-reenactment is not about a single Sunday worship service in isolation from the others. Instead, through a Christ-centered, gospel-shaped liturgy, the gospel story is retold as a drama that spans the course of the full year---the liturgical year (or call it the Christian year). With this integrated approach, the liturgy followed each Sunday is located within the flow of the full gospel story, unfolding over the course of the entire year through its various seasons as shown in this diagram:

As the diagram shows, the Worship Year (in the Western Christian tradition) begins in late November or early December with Advent Season followed by Christmas Season. Then comes the Season of Lent, Holy Week, Easter Season, and then a season called "Ordinary Time"---not ordinary as in unimportant, but because this season of worship addresses day-in-and-day-out Spirit-led responses to the great gospel events celebrated throughout the rest of the year. Those responses involve our participation, by the Holy Spirit, in Jesus' disciple-making mission to the world. Because that participation is led and empowered by the Spirit, Ordinary Time, which follows Pentecost, is sometimes called Time after Pentecost or Season of Pentecost.

When this year-long liturgy is followed, each worship service is themed for the season in which it falls, and in that way is deeply connected to Jesus through the retelling/reenacting of certain aspects of his story (the gospel). Optimizing that connection takes planning and creativity. It also takes time—but it's time well spent because an effective, creative liturgy engages the worshippers at multiple levels: heart, head and hands, helping them to be active participants rather than passive spectators.

The flyleaf of Living the Christian Year: Time to Inhabit the Story of God by Bobby Gross, has this to say concerning the power of liturgy to help people inhabit God’s story:

Remembering God's work, Christ's death and resurrection, and the Spirit's coming will change you, drawing you into deeper intimacy with God and pointing your attention to the work of the Father, Son and Spirit right now, in and around you. You'll be reminded daily that your life is bigger than just you, that you are part of God's huge plan that started before time and will continue into eternity. Keeping liturgical time, making it sacred, opens us further to this power as, year after year, we rehearse the Story of God---remembering with gratitude, anticipating with hope---and over time live more deeply the Story of our lives.I encourage you to think of the worship service each week as a play (drama) with multiple scenes, or as a symphony with multiple movements. Think in terms of choreographing the liturgy accordingly, with movement, pace, building to a crescendo, then dismissal. All parts of the liturgy should interrelate in telling the gospel story in the most memorable way possible, thus engaging the worshippers in the drama. It is through their engagement---their participation in the drama---that their lives will be more and more converted to Christ.

Concerning the Lord’s Supper

In the historic liturgy of the Christian church (in both Eastern and Western traditions, going back the the very early church), the Lord's Supper (Communion) is the high point and focus of each worship service. Some Protestant churches worry that serving Communion every week makes it too common. Some also worry that doing so takes too much time away from the sermon or other worship elements. While these concerns are understandable, consider what T.F. Torrance (in Gospel, Church and Ministry) says concerning how Communion proclaims the gospel in unparalleled ways:It is at Holy Communion above all that we see Christ face to face and handle things unseen and feed upon his body and blood by faith. It is there in the real presence of Christ that we grasp something of the wonder of the Savior’s love and redeeming sacrifice, and understand that it is not our faith in Christ that counts but his vicarious life and sacrifice, his redeeming life and death that count. It is at Holy Communion when the bread and wine are put into our hands, that we know it is not our believing that counts but he in whom we believe, not what we do but what the Savior has done for us and what he means to us. It is at Holy Communion, in short, that we really understand best the gospel of salvation by grace alone. Thus it was at Holy Communion that [as a pastor] I found it easiest to proclaim and make clear to people what the unconditional grace of God’s saving love really is….

I have found in my own ministry that it is easiest to preach the unconditional nature of grace, and the vicarious humanity and substitutionary role of Christ in faith, at the celebration of the Eucharist, where the call for repentance and faith is followed by Communion in the body and blood of Christ in which we stretch out empty hands to receive the bread and wine: “Nothing in my hands I bring, simply to thy Cross I cling.” There at the Holy Table or the altar I know that I cannot rely on my own faith but only on the vicarious faith of the Lord Jesus in total substitution of his atoning sacrifice on the Cross….

That is what the covenant in his body and blood, which the Savior has forged for us, actually, practically, and really means. It is the very essence of the gospel that salvation and justification are by the grace of Christ alone, in which he takes our place, that you may take his place. (pp. 47, 88, 251-252)

Concerning the liturgy for weekly worship

In the classic (historic) liturgy of the church (still used by many churches today), the worship service focuses first on proclaiming the Word (through Scripture reading, hymns and sermon), then it focuses on enacting the Word (through Communion). In that way, what is spoken in addressing the gospel and in praise of the Lord, leads the worshippers to the Lord's Table where the gospel is enacted and the Lord is personally encountered in the unique, powerful way that Torrance notes.As Torrance also alludes to, in the historic worship liturgy, Communion is preceded with a prayer of confession---not to "earn” or somehow “qualify” for the distinctive blessing that comes to us at the Lord's Table---but to acknowledge the need we all have for the grace that Communion represents to people who have placed their trust in Christ. (For further detail and examples of prayers of confession, click here.)

In the next post in this series we'll begin looking at each element in the Christian Worship Year, which, as we've already noted, begins with Advent Season.