Moral police or moral advocates?

This post continues a series in The Shape of Practical Theology by Ray S. Anderson. For other posts in the series, click a number: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13, 14, 15.

Ray Anderson advocates what he refers to as Christopraxis---an approach toward ministry that flows from what he calls a theological ethic. In this post we'll see what that looks like when pastors address the moral crises in our culture. Anderson calls pastors to respond not as moral police but as moral advocates who participate with Jesus in what he is now doing by the Spirit to heal a hurting world.

Jesus interpreted the moral will of God in terms of the goal toward which God's design and purpose for humanity point. The apostle Paul had the same perspective, seeing the ultimate purpose and goal of God for human beings as leading to full equality and parity in the kingdom of God (Galatians 3:28), even if certain accommodations to a lack of equality/parity must be accepted in the present situation.

God's ethic (theological ethics) is, therefore, fundamentally about people and their ultimate best (their salvation). The ethic we embrace and exemplify in extending pastoral care must follow suit if it is to be fully Christ-centered (i.e. Christopraxis). That ethic leads to real participation in the love and life of the God who, in Christ, by the Spirit, remains free to be "with" each person in their particular situation, and through that personal presence lead them toward God's ultimate best for them and all humanity This is what we mean by being moral advocates rather than moral police. More about that next time.

|

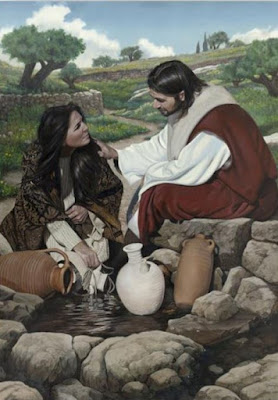

| Woman at the Well by Liz Lemon Swindle (used with permission) |

When it comes to morals, values trump beliefs

It's common for people today to decry the moral decline in our culture. Even those who express belief in a divine being are doing what seems right in their own eyes, rather than what would conform their behavior to a universally accepted moral code. What we see in this is that behavior springs more from personal values than from universal beliefs. Said another way, when it comes to behavior, values trump beliefs. Anderson comments:Personal values are what we spend money, time and energy to achieve or experience. In our culture, behavior reflects values more than beliefs. For example, North American family sociologists Lucy and Dennis Guernsey have suggested that marital compatibility may depend more on common values than on a common belief system (p207).Does this mean that morality, once defined by universal and objective beliefs, now is entirely relative to personal/individual values (preferences)? In a word, "yes." This is a significant (and perhaps troubling), but a reality that pastors must face in our era of increased individualism and cultural pluralism. How should pastors respond? Anderson points us in the direction of Christopraxis grounded in a theological (incarnational Trinitarian) ethic.

What does Christopraxis look like in pastoral care?

Anderson notes that through Christopraxis, pastors join Jesus in addressing the moral crisis with a theological ethic that leads to serving not as moral police (enforcing certain behaviors) but as moral advocates. What does that look like? Anderson offers the example of how God himself related to Cain and his family following Cain's murder of Abel:A basis for a theological ethic in pastoral care can be found in the observation that God intervenes in the supposed moral right of Abel's family to exact vengeance on Cain. The "mark of Cain" is not a banishment from the human social order but a "moral mandate" by which he is to be permitted to live within the human community without fear of retaliation (Genesis 4:13-16). God becomes the moral advocate of one who has himself broken the moral law by his act of fratricide. An immoral act does not disqualify one from the moral advocacy of God. Thus God's moral will can be the basis for moral law and at the same time operate with freedom to uphold the life of the one who has broken the law. God's moral will clearly has a pastoral or redemptive dimension, directing pastoral care in cases where an apparent moral dilemma appears based on the moral law alone (p209, italics added).When pastors operating as a moral policemen face challenging moral dilemmas, they tend to emphasize "laying down the law." But when they operate instead as moral advocates, they base what they do on a theological ethic, which means they seek to serve as advocates of the offenders (sinners) as persons (and an advocate of all other persons involved in the particular situation). In doing so, they will be reflecting the nature and purpose of God as revealed to us in Jesus. Anderson lists some of the foundational principles that give rise to this theological ethic expressed through Christopraxis:

- The character of God, revealed definitively and fully in the person (being) and activity (doing) of Jesus, is the moral basis for God's creation. Morality, therefore, is fundamentally relational---about a person, not a code of law. The morality we see in the person and work of Jesus is grounded in God's own faithfulness, justice, mercy and compassion. Therefore a theological ethic is grounded in these same characteristics, or, better said, participates with God in being faithful, just, merciful and compassionate.

- The moral character of creation is revealed through human beings as God's image bearers---those who are "moral agents, not because of adherence to abstract moral law, but because they bear the very moral character of God" (p210).

- Human character is expressed principally through the moral quality of social relations. As Anderson notes, "The intrinsic value of each person is an absolute moral reality, as each bears the human image of divine moral character" (p211). That image is expressed primarily socially (in community) not individually. Anderson comments: "The character that underlies moral decisions and actions is not the possession of individuals...but the moral quality of core human relationships" (p211). For example, Anderson notes how Paul admonishes us to "be subject to one another out of reverence for Christ," then goes on to give moral/ethical instructions concerning married couples, parents, children, slaves and masters (Ephesians 5:21-6:9).

- The formation of character takes place where personal values are created out of moral experience. Teaching of moral principles in an abstract way will have little effect. Instead we must show through act and word how moral character has personal value. Anderson comments:

The formation of Christian character is not achieved by the teaching of Christian doctrine alone, nor by setting down rigid rules of moral discipline. Rules are necessary to set boundaries, but it is relationship, rather than rules that forms character. When the Bible speaks of character, it does so in terms of core human and moral spiritual values rather than religious rituals and regulations. The crucial moral experiences that contribute to the formation of character do not take place in church meetings but in the family in the primary encounters of people's daily lives (p212, italics added).

Using Scripture in moral instruction

It's common in many churches for the Bible to be viewed as a source of moral instruction---setting forth laws to obey to keep people from immoral behavior. But as Anderson notes, this use of the Bible misses the primary and thus more important purpose for Holy Scripture. Anderson comments:"The Bible is more important for helping Christian community to interpret the God whom it knows in its existential faith than it is for giving a revealed morality that is to be translated and applied in the contemporary world... The Christian moral life, then, is not a response to moral imperatives, but to a Person, the living God... What the Bible makes known, then , is not a morality but a reality, a living presence to whom man responds." [quoting James Gustafson]

The Bible cannot be used as a method of arriving at ethical principles or moral criteria abstractable from the participation of God himself in the moral situation of human life. Or to put it another way, the Bible cannot be used as a substitute for moral freedom grounded in responsibility.

While the Bible clearly gives authoritative status to the will of God as a determining factor in theological ethics applied through pastoral care, the Bible cannot be seen primarily as an ethical textbook, whether prescriptively, instructively or illustratively. There is a wrong use of the Bible in attempts to discern God's will in crucial pastoral situations, as well as a right use (pp213-214).It is a mistake to approach the Bible as a source of proof texts for defining strategies or solutions to modern problems. This was the error of the Pharisees in Jesus' day. You'll recall how they used an Old Testament proof text in passing judgment on the woman caught in adultery. In contrast, Jesus' approach went in an entirely different direction, reflecting not a proof text, but the character of God with an eye toward the future of the woman in the short term and beyond. Jesus theological ethic had a decidedly eschatological perspective that anticipated the ultimate expression of God's will and design for this woman (and all humankind).

Jesus interpreted the moral will of God in terms of the goal toward which God's design and purpose for humanity point. The apostle Paul had the same perspective, seeing the ultimate purpose and goal of God for human beings as leading to full equality and parity in the kingdom of God (Galatians 3:28), even if certain accommodations to a lack of equality/parity must be accepted in the present situation.

Is this situation ethics?

Is the theological ethics that gives rise to Christopraxis a type of situation ethics? In one sense, yes it is---Jesus always adapted himself to the "situation" at hand as he ministered to real people in real circumstances during his earthly ministry, and he continues to make these adaptations as he serves us as our Mediator and High Priest. But his adaptations are not based in changing, ephemeral personal desires/preferences, but on the unchanging character of God who, in Christ, by the Spirit, has accommodated (and continues to accommodate) himself to our situation in order to be with us, bringing us forward toward his ultimate design/purpose/goal for us all.God's ethic (theological ethics) is, therefore, fundamentally about people and their ultimate best (their salvation). The ethic we embrace and exemplify in extending pastoral care must follow suit if it is to be fully Christ-centered (i.e. Christopraxis). That ethic leads to real participation in the love and life of the God who, in Christ, by the Spirit, remains free to be "with" each person in their particular situation, and through that personal presence lead them toward God's ultimate best for them and all humanity This is what we mean by being moral advocates rather than moral police. More about that next time.