Pastoral care as moral advocacy

This post continues a series in The Shape of Practical Theology by Ray S. Anderson. For other posts in the series, click a number: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 14, 15.

As noted last time, Anderson calls upon pastors to serve as moral advocates rather than moral police. He defines moral advocacy this way:

|

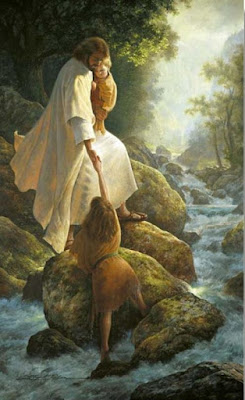

| Be Not Afraid by Greg Olsen (used with permission) |

The extension of divine grace to persons who are guilty of breaking the moral law or who are suffering a loss of personhood through the existence of a structure mandated by moral law. The practice of moral advocacy places on the side of the marginal person the moral right for personal dignity, freedom from abusive relationships, and full parity in social and communal life....

[This advocacy in the form of pastoral care is] provided at times of crisis, when life has become difficult, if not impossible, when relationships have been distorted, if not destructive, and when the tragic contravenes common sense, and even faith fails (p218).Crises come in many forms, of course, including spousal and child abuve (both physical and emotional), the breakdown of a marriage, the sudden death of a loved one, the loss of personal freedom due to addiction, the loss of meaning and purpose experienced by people moving into old age, etc. Because such crises touch at the very heart of what it means to be human, they present moral dilemmas that require moral advocacy from a pastoral caregiver who understands that God's moral will is always directed toward the goal of human life, not an abstract principle of law. The role of the pastoral caregiver is thus to be an advocate of God's moral will for the particular person. That advocacy comes in two ways:

- Being an advocate of God's own presence through the indwelling Holy Spirit. The pastoral caregiver is one in whom the "real presence" of Christ is made manifest as a form of advocacy to and on behalf of the one in crisis.

- Being an advocate for the person's moral freedom to be a whole and functioning human being. The caregiver does not merely come as a moral authority, dispensing the law on behalf of the one caught in the dilemma. Rather, the caregiver comes as an advocate of the moral authority that belongs to the other by virtue of that person's status before God as one who bears the divine image and likeness in fellowship with other humans (see p219-220).

...resolves the moral ambivalence otherwise present in the caregiver [And what caregiver has not felt this ambivalence!]. This advocacy frees the situation from the moral autonomy that offers the "easy out"--my pain gives me a right to get even with the one who hurt me, or, the injustice I have suffered gives me the right to break out of my commitment. At the same time, this advocacy that binds all persons, whether victims of their own immoral acts or of the acts of others, to the moral will of God also sets free those bound by the inhuman laws and practices of others. The person is also thus set free to forgive, which is a moral action related to his or her own goal of healing (p221).I can hear legalists crying, "Situation ethics!!" But theological ethics always takes account of the [human] situation because it is the moral will of God to do so. Said another way, God's moral will always is an extension of his grace, which is for not against people. God, the ultimate moral advocate, in grace always moves toward not away from people. As Scripture says, the letter [the law] kills, but the Spirit [grace] gives life (2 Cor. 3:6). Anderson comments:

[The God of grace] enters into covenant relation with human beings and as covenant partner, aligns himself with them over and against nature [as in the natural consequences of sin].... God's judgment against sin, from the standpoint of theological ethics, is itself a continued intervention of divine grace. For if the sinner were left to the consequences of moral and spiritual disorientation, human personhood would disappear beneath the sickness and turmoil of life...

The moral good of divine grace is manifested by God's intervention for the sake of restoring persons, even if the consequence of sin is viewed as divine judgment. God's judgment may be an expression of the consequences of violating a moral law, but his grace is an expression of God's moral will which has as its goal the moral good of forgiveness (pp224-225).A theological ethic of moral advocacy therefore calls upon us to participate in every case in what God is doing to extend his grace and forgiveness to the persons in crisis--even when the crisis is the result of their own sin. Indeed, the offer of grace to the person though advocacy should not be dependent on a determination of whether or not the person is suffering due to their own sin. As Anderson notes,

Grace is itself God's moral intervention between the person and the consequences of sin, even if that consequence is viewed as divine judgment (p226).The moral advocate also provides for the suffering person a transfer of spiritual power via the empowering of the suffering person to have faith in the moral good available from a good God. This transfer happens as the advocate shares the pain and agony of the one who suffers--this is the ultimate expression of Christian empathy--feeling what the other person feels, even as a consequence of their own sin. This is precisely what Jesus did in taking upon himself our fallen nature with its sin in order to share in our suffering and in doing so to minister God's power to us--his power to heal (save). As Anderson notes,

It is the suffering of God that brings those who suffer into contact with his divine power and goodness... The caregiver reveals the suffering of God through identification with the pain of human suffering, and releases the power of God by bringing God into contact with human weakness and distress. This is an incarnational kind of care giving... (p228).Anderson concludes his chapter on moral advocacy with this statement:

It is the privilege of those who give pastoral care to see indirectly the very glory of the moral goodness of God in the faces and lives of those for whom we are moral advocates (p232).