Words for worship: He is closer to us than we are to ourselves!

This post is from worship leader Mike Hale.

Ever feel a gazillion miles away from God? As worshippers of a God that we do not presently see (or that we see dimly and with ‘spirit eyes’—which is another subject in itself), we can feel as though the living, risen and ascended Lord Jesus is light years away from where we are, and awfully hard to reach—especially if we feel guilty and captive to our wrongs or the situation around us. ‘But remember this’, said my theologian friend John Emmory McKenna (or Dr. John, as I affectionately call him), ‘he is closer to us than we are to ourselves!’

It was a catchy, comforting line, and McKenna has reminded me of it often. First time was 1997 and Dr. John and I were having a much-needed talk about prayer and worship. I was the one that needing the talk, and asking all the questions, generally summed up as, ‘what is God doing when we worship?’

|

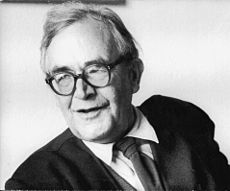

| Swiss theologian Karl Barth |

Long-time readers of this blog may recall mention of that conversation with McKenna, and that he recommended the reading of “Royal Priesthood”, by Thomas F. Torrance, and how McKenna said the theology of T.F.T. and also Karl Barth, would deepen my understanding of trinitarian worship. Well, many years and books later, the reminder that ‘he is closer to us than we are to ourselves’, still strikes me just as powerfully now as it did then, and I’ve used it often in leading worship.

Of course, the line didn’t originate with Dr. John. T.F. Torrance sometimes said it, as did his mentor, the great Swiss theologian Karl Barth, who included the line in short sermons preached between 1954 and 1959 in a Basel prison where Chaplain Martin Schwarz invited him to visit and preach. During a recent trip to my favorite used bookstore I came across an old hardbound volume of Barth’s “Deliverance to the Captives”, containing 18 of the sermons, including opening and closing prayers.

(In the opening remarks Barth writes that in preparing and conducting the worship services, the prayers he prayed were to his mind every bit as essential as the sermons themselves, and he hoped readers would find to same to be true for them while sharing in these services. Perhaps we can discuss some of these prayers in coming posts.)

While the academic writings of Barth often require that readers take small bites, chew carefully, and allow ample digestion time—not so with these plain-spoken, challenging, yet comforting and joyous sermons, which in this case were preached to prison inmates—an admittedly not-too-Christian audience.

The book begins with Barth’s August 1, 1954 sermon on Psalm 73.23, ‘Nevertheless I am continually with thee; thou dost hold my right hand.’ Barth explains to these prisoners that when we gather for worship, we are celebrating freedom, including the freedom to proclaim that we are not alone—that rather we are continually with the one person that brings light so the blind can see, brings bread to the starving, and water to those dying of thirst. He then draws our attention to the person we are said to be with—the one holding our right hand.

What kind of a ‘thou’ is this? Is it a man? Yes, indeed someone with a human face, a human body, human hands and a human language. One whose heart bears sorrows—not simply his own, but the sorrows of the whole world. One who takes our sin and our misery upon himself and away from us. One who is able to do this because he is not only man, but also God, the almighty Creator and Lord who knows me and you much better than we know ourselves, who loves me and you much more than we love ourselves. He is our neighbor, he is closer to us than we are to ourselves, and we may call him by his first name.

And asking ‘do you know who he is’?, Barth quotes a line from a Martin Luther, ‘Christ Jesus is his name’ (from ‘A Mighty Fortress’). Barth then reminds us that none of this is accomplished by us—not by our own strength. We cannot hold onto God. We may be asked to reach out and extend the right hand of fellowship to others, but not to the Lord God. There is no need, as He already holds our right hand in his right hand.

Remember, Barth is here addressing prison inmates—who know they are captive and may feel far from God after having done things wrong in their lives. In order to hear Barth’s gospel message that day, each one had to break the law and be thrown in prison. Yet as is stated in the preface of the book, the real prison is in the heart of us all, and the author addresses himself and all dying humanity as those redeemed from death by the gracious act of God. Barth speaks of loneliness, struggle, sorrow and misery, and brings the message of sympathy, comfort, forgiveness, freedom, grace and joy found only in the One who is closer to us than we are to ourselves—Jesus!