The descent of Jesus (part 2)

This post continues a series exploring Raising Adam, Why Jesus Descended into Hell by Gerrit Dawson. For other posts in the series, click a number: 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8.

Last time, we noted the declaration of the Apostles' Creed that Jesus "descended into Hell." We pointed out that "Hell" translates the Greek word "Hades" and its Hebrew equivalent "Sheol," and that a better English translation is "realm of the dead." We then noted that Jesus' descent to the realm (condition) of the dead occurred on Holy Saturday, the day after Jesus' crucifixion on Good Friday, and the day before his resurrection on Easter Sunday. But what happened to Jesus on Holy Saturday? And why is that important for our salvation? This post presents some of the answers that Dawson offers to these important questions.

The foundation of biblical testimony

Dawson begins by laying a biblical foundation upon which to ground our understanding of what happened to Jesus (and through him to all humanity) on Holy Saturday. According to Dawson, that foundation consists of five key elements of biblical testimony:1. Jesus' prediction that rather than being resurrected directly from the Cross on Good Friday, he would descend to the dead and then, after three days, rise again (Mark 8:31, cf. Matt. 17:22-3; Luke 9:22; John 2:19, NRSV).

2. Biblical declarations that Jesus was raised from the state of being dead. Dawson notes (p. 24) that Jesus' "body was raised from the tomb only when his spirit returned from Sheol" (as we saw last time, "Sheol" is the Hebrew word for what is "Hades" in Greek, both meaning "realm of the dead.") It's important to note that Scripture speaks of death as the separation of the human spirit from the body. It also indicates that prior to Jesus' resurrection, the spirits of people who died were kept in Sheol, while their bodies decomposed on earth. As Dawson notes, rather than thinking of Sheol as a "place," Scripture leads us to view it as a spiritual state or condition. The point to note here is that from the time Jesus died on the Cross until the moment of his resurrection, he shared to the full "the common human experience of disembodied afterlife" (p.24) -- life in Sheol (Hades).

3. Peter's comment in his Pentecost sermon (Acts 2:27, KJV), where he ascribes to Jesus the words of David in Psalm 16 that God would not abandon Jesus' soul to Hell (Hades/Sheol) or let His Holy One see corruption. Though Jesus experienced to the full what it means to die as a human (including descending to the realm of the dead), God did not abandon Jesus to that "place" (condition), but raised him up. But before his resurrection from the dead, Jesus experienced the separation of his spirit (soul) from his body (Psalm 116:3) just as all humans do at death -- a condition that, for Jesus, lasted from late Friday afternoon until early on Sunday. For the rest of us, that disembodied condition (called the "intermediate state") lasts from death until the time we are resurrected at Jesus' return at the end of the present age.

4. Paul's references, including in Romans 10:7 (NRSV) where the apostle asks, "Who will descend into the abyss? (that is to bring Christ up from the dead)." Paul's point is that this question is irrelevant because Jesus, having descended into the state of the dead (the "abyss") has been raised -- he no longer is to be found there. Dawson comments: "The abyss was death in the profundity of its distance from any experience of the presence of God" (p. 25). Paul refers to Jesus' time in the "lower parts of the earth" in Ephesians 4:9 (NRSV), where the Greek word translated "lower" (katotera) is used in the Greek version of the Apostles' Creed to affirm that Jesus truly did descend to the "netherworld of the dead."

5. Sheol imagery found in several psalms and elsewhere in the Old Testament. This imagery helps us understand the reality that Jesus experienced during his time in Sheol. Jesus voiced several of these psalms (e.g., Psalm 30:3; 18:4-6; 49:15; 116:3-4), the Psalter being his prayer book. Jesus recited these psalms with a growing understanding that what they say about Sheol (even if metaphorically) address what he would experience upon death. Dawson comments: "As Jesus takes up these prayers, new depths of meaning open with them" (p. 26).

Interpreting the testimony

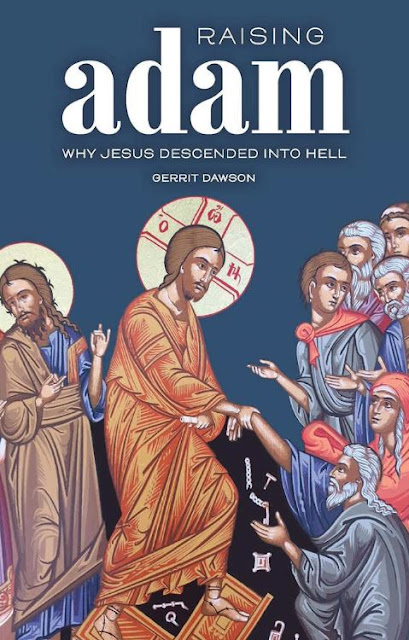

Concerning how this biblical testimony is to be understood, Dawson points out three major streams of theological interpretation that have existed for much of Christian history:1. Descending into triumph. As shown on the cover of Raising Adam (see picture above), the early church understood that "Jesus descended into the dead in order to raise all of mankind who would trust him, as symbolized by raising Adam" (p. 28). Having conquered Satan and death on the Cross, Jesus descends to Sheol as a victor (see Hebrews 2:14-15). Dawson comments:

The entry of the Living One (Rev. 1:18) into the realm of the dead destroyed it. Having broken its power, Jesus descended to the underworld in order to liberate all the souls of the dead who had been awaiting a savior. This is classically known as the harrowing of hell. Jesus plundered death of its spoils and the devil of his captives, setting us free for everlasting life. (p. 28).

[Jesus] went down to the root, to the origin, of human nature. All the way to the first man. To dig beneath our sin. To undo the fall. To raise up all that had been lost. Resurrection after such a descent meant haling us from the inside out. This was not only a salvation worked out above us in a heavenly ledger but within our fallen nature as well. As one of us, Jesus the Son of God was lifting us up to his Father in the Holy Spirit. (p. 29)This understanding draws on 1 Peter 3:18-19 in which Jesus "put to death in the flesh but made alive in the spirit... proclaimed to the spirits in prison." This then is connected to the statement in 1 Peter 4:6 that "the gospel was preached even to those who are dead," leading to the understanding that the rising Jesus liberated the dead souls who had awaited him.

2. Hell on the Cross. Some who are skeptical about the interpretation given above, prefer to think of Jesus' descent into Hades as happening while he hung on the Cross. They see this indicated by Jesus' cry of dereliction during that time: "My God, my God, why have you forsaken me" (Matt. 27:46). According to this interpretation (which was advanced by John Calvin), on the Cross, Jesus bearing the full force of judgment against sin, underwent the hell of damnation as our substitute. Thomas Torrance provides another take on this interpretation, writing in Theology of Reconstruction (p. 124) that the crucified Jesus

answered for us to God; even in his terrible descent into our God-forsakenness in which he plumbed the deepest depths of our estrangement and antagonism, he reconstructed and altered the existence of man, by yielding himself in perfect love and trust to the Father. (Dawson, p. 30)Those who embrace this interpretation, tend to relegate what Jesus did on Holy Saturday to the realm of mystery.

3. Solidarity with the dead. This interpretation emphasizes that during Holy Saturday, Jesus entered what theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar called a "solidarity in nontime with the dead" -- an "entry of the soul into the passive, helpless, free fall state of being dead" (p. 32). According to this view, through his time in Sheol, Jesus took the side of sinners even in death (death being the consequence of sin), thus accepting fully our condemnation. Dawson explains:

Jesus' descent to the ream of the dead during Holy Saturday assures us that God who has wed himself to our humanity stays with us not only to the end of the age but even through the dark passage of death, even through the deep suffering and sorrow of this present age. (p. 33).Rather than seeing these three streams of interpretation as mutually exclusive, Dawson suggests that they can be integrated, providing this understanding:

The event of Christ's descent into hell touched his dying, his being fully in the state of the dead, and his rising from the dead in glorious resurrection. To put it another way, the descent was a bridge event. It is not only the gap between cross and resurrection, but the vital link between them. It is the "place" where the turn is made from defeat to victory and Holy Saturday partakes of both.... [Jesus] descended fully into our death, both spiritual and physical. But in doing so, he laid hold of us at the deepest point of our estrangement from God. He descended in order to raise us up with him in resurrection life.... Jesus went farther from the Father than Adam had fallen. He journeyed, as it were, back before the first sin, down to the root of our creation. Then, he raised Adam. Jesus grabbed the man who represents our human nature and condition. Jesus went down, got Adam and took him with him as he rose. The new, last Adam, redeemed the first Adam.... Jesus completed the recreation of our humanity in the place of the dead, in hell; in rising, he raised us also. This is what it means that Jesus descended fully into our death in order to raise us fully into his life. (pp. 34-5)Here is another illustration of Jesus' descent into Sheol, followed by his ascent in resurrection, lifting up humanity out of Sheol as he went:

|

| The Harrowing of Hell by Albrecht Durer (public domain via Wikimedia Commons) |