Reader’s Guide: T. F. Torrance, “The Sovereign Creator”

In this post, Kerry Magruder provides a reader's guide to "The Soveriegn Creator," which is chapter 8 of Thomas F. Torrance's book "The Christian Doctrine of God: One Being Three Persons" (1996). The guide was written for a session of the T.F. Torrance Reading Group.

Introduction (pp. 203-204)

“While the concept of God as the Creator of the universe derived originally from the Old Testament revelation and had been developed by Judaism, it was radicalised through the New Testament teaching about the Lord Jesus Christ as the Word of God by whom all things that came into being have been created, from whom they derive their intelligible and lawful order, and through whom and in whom the whole universe of visible and invisible realities consists or is held together. In Jesus Christ the Lord God has himself become man, and the Creator of all things has himself become a creature, without of course ceasing to be God the Creator, and therefore interacts creatively with the world not just from without but from within. And so it is in Christ that we creatures may meet with the Creator face to face, and it is in and through his life and work within the creation, not least through his redemptive triumph over all evil and darkness in his resurrection from the grave, that we may really understand something of the wonderful nature and work of the Creator himself, as it would be quite impossible otherwise. Moreover, since it is in the life and work of Jesus Christ that God has been manifested to us in his reality as Father, Son and Holy Spirit, our knowledge of the Sovereign Creator may not be abstracted from the incarnate power of the saving love of the triune God mediated to us and activated among us in salvation history or from the creative power of the Holy Spirit poured out upon all flesh who sheds abroad that love of God in our hearts.” (The Christian Doctrine of God, pp. 203-204)

Discuss: What does Torrance mean by the radicalization of the doctrine of creation by the gospel? How does this relate to the Christological hymn of Colossians 1:15-20?

Discuss: Is it possible for a Christian to hold to an understanding of the Sovereign Creator that is functionally unitarian? What might a functionally unitarian understanding of the Creator or creation look like? Would it be faithful or accurate?

Discuss: What would it mean for Christian knowledge of “God and nature” today if we were resolved to adopt a Trinitarian or Christocentric approach; “no creation without Christ”? What might this mean for thinking about the Bible and science? For natural theology? For natural science?

1. The Almighty Father (pp. 204-221)

Divine omnipotence

“Thus we do not define God by omnipotence but define omnipotence by the Nature and Being of God as he has revealed himself to us in his creative and redemptive activity…. There is and can be no valid or meaningful discussion of God’s sovereignty or power… in abstraction… from his being God the Father.” (pp. 204-205)

Discuss: William Ockham attempted to think out the doctrine of creation consistent with the first line of the creed, “I believe in God… Almighty.” The doctrine of divine omnipotence and divine absolute freedom became a central theme in late medieval and early modern natural science. What would it mean for us today to adopt a Trinitarian framework instead? How might we critique and improve upon Ockham and the tradition of divine omnipotence in science?

A perichoretic and homoousial understanding of God the Father

“‘Father’ is understood in a twofold but indivisible way, as referring both to the Godhead, and to the Father of the Son.” (p. 205)

Discuss: What is the significance of this statement? How does it relate to the title of this section, “The Almighty Father”?

Love vs. abstract omnipotence

“Within this trinitarian perspective, the power or almightiness of God is revealed to be essentially personal, defined by God’s triune Nature and Being as Father, Son and Holy Spirit. This personal power of God is not power that overrules the creature but sustains the creature, not power that negates the freedom of the creature, but the power of the Love that God is, power therefore that sustains the relation and freedom of the creature before God, for it is always creative, and in relation to his human creatures always personalising and humanising power. It is essentially being-constituting, creature-constituting power.” (p. 206)

Discuss: What are the perils of invoking the “Almighty God” in our thinking, distinct or separate or apart from the Fatherly love of God?

(a) God is always Father, not always Creator (pp. 207-209)

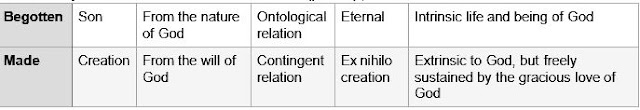

Two entirely different relations with the Father (p. 207):

Discuss: How would a Christian respond to the question “What was the nature of God before he was the Father of Christ?” What is the false premise of that question?

Discuss: Is Torrance’s point here related to how he elsewhere quotes Athanasius: “It would be more godly and true to signify God from the Son and call him Father, than to name God from his works alone and call him Unoriginate” (e.g., CDG p. 117, or Trinitarian Faith, p. 49)?

Discuss: How does this view differ from those of Origen, process theology, idealist or Hegelian theologians, and other perspectives on the relations between God and nature?

Discuss: Why was it radical in the Hellenistic world for early Christians to proclaim that becoming Creator was something new even for God? How does the claim that God, in his divine freedom to love, can become something new, even for him, relate to belief in the Incarnation, or to our understanding of Pentecost?

“By his very nature, in the unlimited, uninhibited overflow of his love and grace, God always takes us by surprise, the ever-living, ever-moving, eternally new Lord God Almighty, the one Source and Lord of all being whatsoever.” (pp. 208-209)

Discuss: How does this understanding of God’s dynamic love affect our lives on a practical and experiential level? Does it also have relevance for our understanding of the life or history of nature?

(b) It is as Father that God is Creator, not vice versa (pp. 209-212)

“The fact that God is always Father, not always Creator, but became Creator, means that it is precisely as Father that he is Creator, and not that he became Father because he was Creator.”

Discuss: What are the implications of this for revisions of liturgical prayers or worship affirmations today?

Discuss: What is lost when “God the Father Almighty” is contracted in our thinking to “God Almighty”? (Cf. discussion question on Ockham, above.)

Discuss: What might it mean for our approach to creation to realize that creation arises out of the eternal, dynamic love of the Father for the Son?

“the actual creation of the universe in the outward movement of the Father’s love was proleptically conditioned by the incarnation of that love within it…” (p. 210)

Discuss: What might this mean for our approach to creation?

“… in his eternal purpose the immeasurable Love of God overflowing freely beyond himself which brought the creation into existence would have become incarnate within the creation even if we and our world were not in need of his redeeming grace.” (p. 210)

Discuss: Torrance earlier in this paragraph disavows what is commonly known as “the Scotist hypothesis,” i.e., that the Incarnation was part of God’s original plan for creation even had there been no fall. Yet in what qualified sense, or with what caveats and qualifications, does he affirm something similar of the impact upon our thinking of the boundless love of God in creation and Incarnation?

“Far from being some irrational arbitrary power in itself…. The relation of God to the world… is never anything else but creative…” (p. 211)

Discuss: How does Torrance help us avoid capricious conceptions of divine omnipotence?

(1) The Activity of God the Father (pp. 212-213)

The rational order of the creation is grounded in “that ultimate Love which God the Father is.”

Discuss: What does it mean for the creation to be the “theater of the glory of God”? What is our role to bear witness to that glory, and to voice the creation’s praise of God?

(2) The Activity of God the Son (pp. 213-216)

“My Father is working still, and I am working” (John 5:17, cited on p. 211)

“In Jesus Christ none other than the Creator, the ultimate Ground and Source of all being, order and rationality, the Creator Word of God who is God, has himself become man within our creaturely existence and operates creatively within it imparting to all things their form and order.” (p. 213; cf. John 1; Col 1; Heb 1)

Discuss: What is the relation between the natural order and the love of God?

“Thus the biblical revelation of God as the ever-living and ever-acting Lord is finally established for us by the incarnation of the Word by whom all things are made, by the personal Presence of God himself in space and time, and his redemptive and providential interaction with the world. This interaction is not to be thought of as involving a suspension or interference in the natural order of things, for the natural order came from the Word of God in the first place, and is now to be regarded as brought under the reordering activity of God through the redemptive intervention of the Creator Word and given a deeper dimension in which it reaches its fulfilment in God’s eternal purpose of Love.” (p. 214)

Discuss: If we think of God and nature deistically, that is, as two separate entities, it is then common to go on and imagine that any interaction between them would be a supernatural interference with, or intervention into, the natural order. Why is this a distortion of a Christ-centered understanding of miracles and of God’s relation with nature?

“It is, then, in Jesus in whom the Creator himself became a creature, God became man, that the mystery of his creative activity really becomes disclosed to us. It is the new creation effected in the midst of the old, inaugurated in Jesus’ birth of the Virgin Mary and consummated in his resurrection from the dead, that opens our understanding to the unique nature of God’s creation and the distinctive activity of his Holy Love within it. It is in Jesus the Saviour and Redeemer of the world that we learn how the Sovereign Creator operates, for in him the almighty power of God’s Holy Love is revealed as omnipotent Grace.” (p. 214)

Discuss: A generation before Darwin’s Origin of Species, Tennyson wrote of “nature red in tooth and claw.” How does a Christ-focused approach to creation help us understand and cope with the disorder, brokenness, and evil in the natural world? Why is it important for us to remember that we see creation aright only in light of Christ and his redemptive work?

• The Incarnation (p. 214-215)

“This is the new act of the eternal God whereby God himself becomes man without ceasing to be God, the Creator becomes creature without ceasing to be Creator, the transcendent becomes contingent without ceasing to be transcendent, the eternal becomes time without ceasing to be eternal. This is an even more astounding act than that of the creation of the universe out of nothing, for in the incarnation the almighty living God becomes little without ceasing to be the mighty omnipotent eternal God.”

Discuss: How does the mystery of the Incarnation require the cultivation of imagination? “The sovereignty of God is here revealed to be omnipotence clothed in littleness…”

Discuss: How does the Incarnation challenge our thinking about divine omnipotence?

• The death of Christ (p. 215)

Christ “penetrates back through the guilt-laden irreversibility of time… in such a way as to undo the past…. This is an act of astonishing divine omnipotence in which God reveals that he loves us more than he loves himself…”

“What God’s omnipotence really is we learn from the identity between the almightiness of God and the weakness of the Man on the Cross – that is a revelation of the distinctive kind of power that God is, which is the very opposite of what we would think or could ever imagine.”

Discuss: How does the death of Christ challenge our thinking about divine omnipotence?

• The Resurrection of Christ (pp. 215-216)

“God has demonstrated for us in the death and resurrection of Christ the altogether distinctive kind of power his omnipotence is, which is so unique that we cannot describe it by analogical reference to any other kind of power. The omnipotence of God is to be understood, as far as it may be by us, only out of its own uniqueness…”

Discuss: How does the Resurrection of Christ challenge our thinking about divine omnipotence?

Discuss: What does it mean to believe that “God is not limited by the incapacity or limited ability of his creatures”?

Summary:

“The incarnation was not just a transient episode in the interaction of God with the world, but has taken place once-and-for-all in a way that reaches backward through time and forward through time, from the end to the beginning and from the beginning to the end.” (p. 216)

Discuss: Is the Incarnation a model for the relation between God and his creatures, between God and nature? If so, how?

(3) The Activity of God the Holy Spirit

“In the Nicene Creed the Holy Spirit is spoken of as ‘the Lord and Giver of Life’ which is linked in triadic formulation of the Faith to statements about the creative work of the Father and of the Son. The Holy Spirit shares in the Sovereign Power (βασιλ∊ία) of the Father and the Son, but his distinctive sovereign activity is that of quickening or giving life to the creature. That is to say, while there is only one creative activity of God, from the Father, through the Son and in the Spirit, the special work of the Holy Spirit is to be discerned in that he brings the life-giving power of God to bear upon the creature in such a way that through his immediate presence to the creature and in spite of its creaturely difference from God he sustains it in its being and brings its relation to the Creator to its true end in him. This is what St Basil called ‘the perfecting cause’ of the Spirit, or the sovereign freedom of the Spirit.” (pp. 217-218),

Note: Torrance is quoting Karl Barth (CD I.1, p. 450 and 472): “The Spirit of God is God in his freedom to be present to the creature, and therefore to be the life of the creature. And God’s Spirit, the Holy Spirit, especially in revelation, is God himself in that he can not only come to man, but also to be in man, open up man and make him capable and ready for himself, and thus achieve his revelation in him.”

Discuss: How does the activity of the Holy Spirit challenge our thinking about divine omnipotence and freedom?

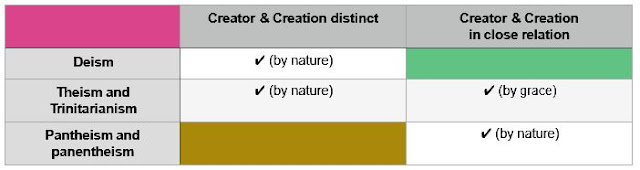

Note: this table is from Magruder's presentation, “Imagining God and Nature.” It is found at kerrysloft.com (search for “Love and the Cosmos”).

Discuss: Contrast the Trinitarian view with a deistic disjunction between God and creatures, on one hand, and with a pantheist union of God and creatures by nature, on the other.

In connection with the activity of the Holy Spirit, Torrance shifts his emphasis slightly from divine omnipotence to divine freedom, and the corollary of the contingent order of created reality.

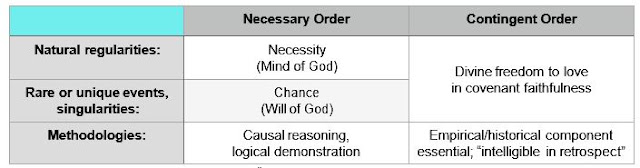

Note: this table is from Magruder's presentation, “Divine Freedom and Contingent Order,” It is found at kerrysloft.com (search for “Love and the Cosmos”).

Characteristics of contingent order (p. 217): not necessary but might have been otherwise; not self-explaining or self-sustaining; open rather than closed; incomplete or inexhaustible rather than exhaustive; dynamic, ever-new, and surprising rather than static or essentialist; not predictable on the basis of logic or causal reasoning; yet nevertheless intelligible and meaningful, anchored or grounded in a transcendent divine rationality, rather than irrational and capricious.

Discuss: How does contingent order differ from necessity? How does contingent order differ from chance? How is contingent order an expression of divine freedom to love?

Discuss: On this view, the universe is contingent and not self-sustaining. Do we therefore have reason to fear that physical reality will collapse and come to an end in utter annihilation?

One corollary of the Holy Spirit’s activity in divine freedom to love is the authentic, contingent freedom of creaturely being: “That is the aspect of God’s triune Sovereign Power which has to do particularly with the liberating and quickening activity of the Spiritus Creator whereby the creature is creatively upheld and sustained in its existence beyond its own power in an open- ended relation toward God in whom its true end and purpose as creature are lodged.” (p. 217)

Read: With reference to the secret of creation revealed in Christ, Torrance quotes Ephesians 1:3-14.

Discuss: Is the Christian vision of nature ultimately one of “love and the cosmos”?

Torrance cites Barth’s description of the history of creation as a “temporal analogue” of the activity of Trinitarian love, so that we might expect nature to bear an imprint of the Trinity upon it. Torrance continues: “This is not to be thought of in terms of an analogy of being (analogia entis), for the Creator and the creation are ontologically utterly disparate, but it does mean that in the wonder of his free out-going love and grace the universe took form as a created counterpart to the uncreated movement of Love within the Holy Trinity. What may be envisaged is an analogy of relation (analogia relationis)’, that is a created correspondence in the relationship between the eternal generation of the Son within the life of the Holy Trinity (begotten, not made), on the one hand, and the relationship between the creation of the universe (made not begotten) outwith the life of the Holy Trinity, on the other hand. It is not to be understood, therefore, in terms of analogical relations on one and the same logical or ontological level, but rather in terms of meta-relations or cross-level relations.” (pp. 219-220)

Discuss:

(a) How does this differ from natural theology in a traditional, foundationalist mode? [Christ-centered, Trinitarian, contingent, personal, dynamic, stratified or meta-relational, faith-seeking-understanding, non-dualistic, etc.]

(b) Why is this enterprise of correlation brought up in a section devoted to the activity of the Holy Spirit?

2. Divine Providence (pp. 221-234)

“In [Jesus] we find that God does not exercise his sovereign Power upon us from above and beyond us like some impersonal force majeure, but in an intensely personal patient way from below, by penetrating into the dark disordered depths of our alienated creaturely existence in order to work savingly, healingly and preservingly within it.” (p. 222)

Discuss:

a) How is providence, like creation, a Trinitarian activity?

b) How does a Trinitarian understanding of Providence challenge our conceptions of divine omnipotence?

c) How do the first pages of this section on providence recapitulate and build upon the previous sections?

“In his relations with the world the unlimited freedom of God in his transcendent rationality and the limited freedom of the world in its contingent rationality overlap and intersect in such a way as to give rise to refined and subtle patterns of order in the on-going spatio-temporal universe which we cannot anticipate but which constantly take us by surprise.” (p. 222)

Discuss: Does providence partake of the character of contingent order and divine freedom to love, as we saw for creation?

Torrance speaks of providence as God’s activity in preserving, conserving, sustaining, and upholding creation. Providence is God’s immanent life-giving activity, caring for creatures, providing and redeeming them, fulfilling his purpose of love and grace revealed in Jesus Christ. He is not an “absentee God,” “deistically detached,” but is personally present and near to us.

Mystery of evil (pp. 224ff.): “In his transcendent freedom God exercises his providence over all that inexplicably defies his ways or seeks to make itself independent of him – that is, he exercises his lordship over all evil and death, but it is a lordship not of naked power but of his love and grace and in patient and wise fulfilment of his purpose of redemption and renewal.”

Discuss: Torrance refers to evil as “not just privative but directly negative in its character.” (p. 224)

Discuss: How does Torrance discern a relation between the cry of dereliction on the cross and the continuing Trinitarian activity of providence? (p. 225)

Discuss: Torrance describes God vanquishing evil “from within” (p. 225). What does he mean?

(1) Human existence and history are not separable from the material universe.

Discuss: Is Christianity a cosmic religion, and not merely a spiritual vision? Is it essential to a Christian conception of providence to envision “a radical change in the material world” and the “complete redemption of the created order”? Will “all things, material as well as spiritual,” eventually “serve his purpose of eternal love”?

(2) By its very nature, moral or natural evil is essentially anarchic.

Discuss: Is there any reason for evil? Or does evil defy rational explanation?

Discuss: Is our conflict with evil personal, involving a conflict of wills?

(3) By its very nature evil has a kind of impossible, though a deadly real, existence.

“In its cunning duplicity evil takes cover under the good and the right and uses them to exert its malevolent force against God and his good creation. As such evil has infected and is somehow present throughout the whole realm of material and spiritual reality.” (p. 228)

Discuss: How is it that evil has an impossible, though real, existence?

Discuss: Is it wise to say that God permits evil?

Discuss: How does the cross give us hope that God will completely heal all the devastating effects of evil upon us? (p. 228)

Discuss: How is providence related to the existence and work of the church? (p. 229) Discuss: How is providence related to the existence and work of angels? (pp. 229-233)

Conclusion (pp. 233-234)

“Here there can be no deterministic notion of providence whereby all things are ruled in accordance with rigidly imposed laws, but one through which God reaffirms the contingent nature of his creation with a relative independence and freedom and order of its own, while re- establishing its coexistence with himself. This means also that we may not think of the ongoing universe as somehow at the mercy of blind chance and irrational process, which would be merely the obverse of a thoroughly fatalistic and determinist conception of the world. Nor may we think of it as furnished by God with such an independent order and self-consistent set of rational laws that it is entirely self-governing in all its immanent processes and changes. Rather must we think of the created universe in its covenanted relation to God as in itself incomplete and open-structured, with built-in freedom and unpredictability characterising its essentially contingent nature which cannot be understood consistently through necessary modes of reasoning. As Creator and Redeemer, God alone holds the key to the mystery of the ongoing created order. We must think of its history as one in which God’s unlimited freedom intersects with and overlaps with the relative independent reality and contingent and limited freedom of the world, in such a way as to make all that happens serve the purpose of his love and reflect his divine glory.” (p. 233)

Discuss: How does this paragraph recapitulate the themes of divine freedom to love and contingent order?

Discuss: Torrance argues that we cannot understand the “how” of creation and providence any more than the virgin birth, Resurrection, or new creation. They are all alike uniquely and distinctively Trinitarian acts beyond our comprehension. Why does this point need to be made?